Great Britain was isolated and alone.

The United States had not yet entered the war. Germany had already conquered Norway, Poland, Denmark, Luxembourg, and France. Britain stood alone, as an island, and it was now their turn. Operation Sea Lion, Germany’s planned invasion of Britain, was underway. The Germans were ready to invade.

Italy’s support for Germany was an unmistakable signal.

So what did Britain do? It became even more fearful. Churchill, influenced by a media campaign referencing the invasion of Norway—where there had been an internal movement that had undermined the resistance and helped the Germans—gave an order. There was a term for this: a “fifth column”.

Even the British believed that a “fifth column” might exist within their own country. It didn’t exist, it wasn’t real—but they believed it. And so they built up this idea that the fifth column was made up of the Italians living in Britain. Italians living in Britain? They were all assumed to be fascists. So: arrest the fascists and remove them.

A simple equation, born out of fear.

It was all fear—not that it should be justified, but it should be understood. Britain was alone and feared collapse. Churchill declared: “This is our darkest hour.” There’s even a beautiful film that says exactly that. America had not yet entered the war, and so Britain had to take extraordinary measures, in direct response to the declaration of war. The order was given: arrest them all, grab them all, collar them—no exceptions.

They already had lists—compiled from every Italian club, most of which were linked to the fascist “Case del Fascio” (Fascist Houses). But let’s be honest: the Case del Fascio in Liverpool, Manchester, London—even Glasgow—weren’t the same as the ones we had in Italy. They were simply Italian community centres. People didn’t talk about politics there. Politics in Rome felt distant. Yes, they were called “Case del Fascio” because that was the government in Italy—but really, they were just gathering places for Italians.

The British had the full membership lists. And their equation was this: Italian club = Fascist = Sympathiser = Possible Spy. So: arrest them all.

They were seen as potential saboteurs.

This idea of rounding up potential enemies wasn’t isolated. The same thing happened in the United States with the Japanese, as I wrote in my piece. After Pearl Harbor, the Americans rounded up Japanese residents—even on the Hawaiian Islands—and sent them to internment camps.

We Italians did the same thing to the British in Italy, though there were fewer of them. Some were even taken to Villa Basilica—six Maltese people—because they were seen as potential enemies or sympathisers.

But here’s the tragedy: the Italian community in Britain was extremely well integrated. They lived there. Their children went to school with English children. On the morning of June 11 (following Mussolini’s declaration of war on June 10 at 6:30 p.m. from Piazza Venezia), arrests began. Everything had been prepared in advance. The arrests were immediate.

Even the British police officers were embarrassed—they had children playing football with Italian kids, families living side by side, renting homes from each other, working together. They didn’t know how to explain it.

So the arrested Italians were taken to internment camps—former barracks, airfields, any available public space. They were packed in. Then, from those places, many were sent abroad—to Canada, to India, scattered around the globe. The British Empire had colonies, and Canada initially offered 4,000 spots.

The first ship was the Duchess of York, a slightly smaller vessel that carried 2,000 people and made it safely to Canada.

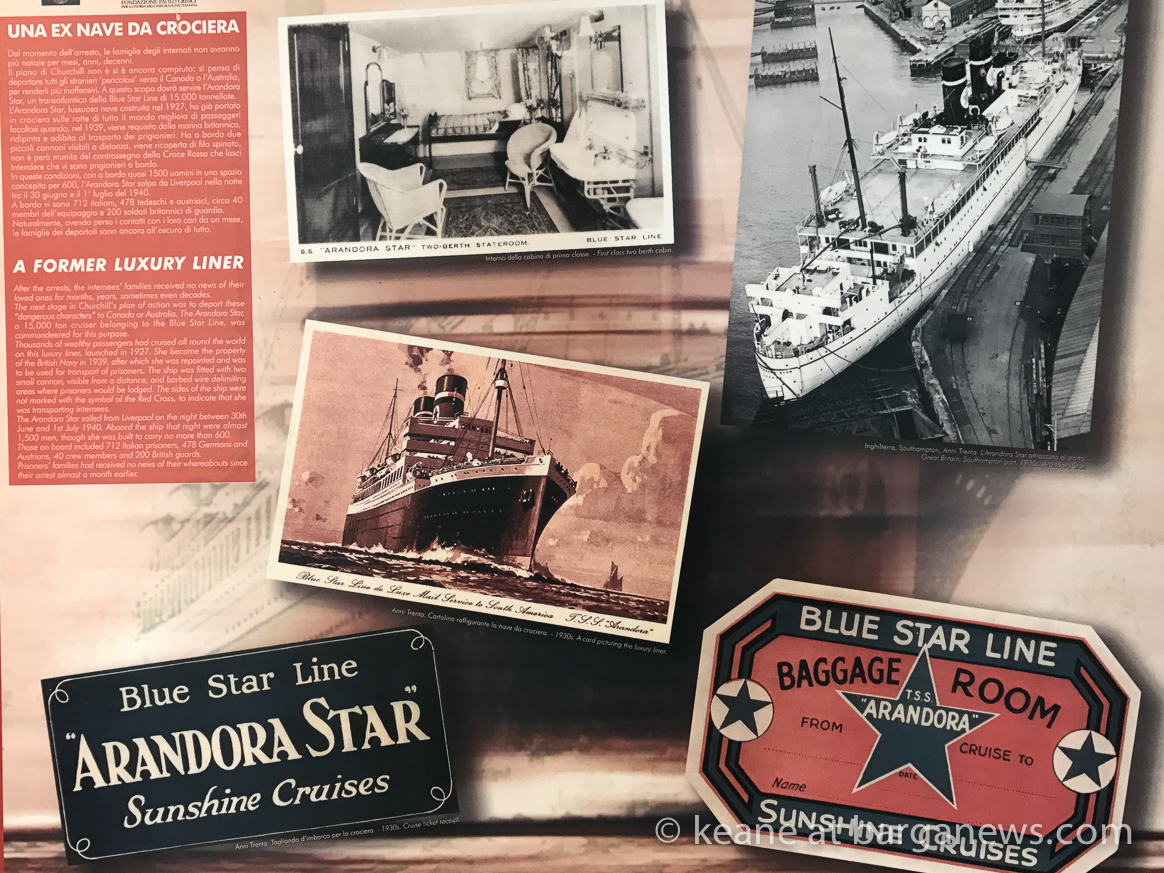

The second ship—this is where things turn tragic—was the Arandora Star, a former luxury cruise liner, fitted with more powerful engines and even a swimming pool. It had been requisitioned by the military, like many civilian ships during the Dunkirk evacuation. Civilian vessels were militarised by the Royal Navy.

In the British maritime tradition, merchant and military navy uniforms, ranks, and structure are the same. The only difference is the crown on the military flag. The Arandora Star was fitted with two artillery guns—one fore and one aft—making it a military vessel.

It wasn’t a warship, not a frigate or corvette. It didn’t have reinforced hulls or heavy armament. But with two guns mounted, it was officially a military vessel. About 1,500 people were on board: 900 prisoners, 200 military guards, and 180 crew. Numbers vary slightly due to inconsistent records—names were handwritten, and often misspelled due to phonetic errors.

The ship departed for Canada.

Here we must dispel some myths. Thanks to documents found by researcher Balestracci and eyewitness accounts, we know that the stories of prisoners being treated like animals, stuffed below deck behind barbed wire, are largely untrue.

The ship’s captain objected to the dangerous overcrowding. He knew it was unsafe. He resisted orders to take more passengers—he knew they only had 14 lifeboats. He was ordered to take 500 more people but negotiated with the military commander to avoid it.

The ship sailed in a zigzag pattern to avoid submarines—standard naval manoeuvres. It travelled with lights off, like a warship. It had no merchant markings. The artillery pieces were cordoned off with barbed wire—not to confine prisoners, but to prevent access to the guns.

The prisoners could sleep outside if they wished. They were not locked in cabins. But the ship was overloaded—more than double capacity.

On the morning of July 2nd, the Arandora Star was spotted by a German submarine—U-47, a modern Type VIIB U-boat. It was commanded by Günther Prien, a celebrated German naval hero. He had previously infiltrated Scapa Flow and sunk a British battleship.

He had already sunk several ships and was returning to base with only one torpedo left—and it was faulty. Its impact fuse was damaged. His crew discussed the risk but ultimately decided to use it.

Before firing, Prien correctly identified the Arandora Star as a military vessel. Both he and his first officer reviewed its profile in their naval registry. They saw the guns, the silhouette, and agreed it was a legitimate military target.

Prien followed orders. He did his job. He believed he was attacking a warship. He cannot be blamed.

But the British government, on the other hand, was clearly negligent. Their handling of the voyage was sloppy. Too many people, not enough lifeboats—only 14, two of which were destroyed in the explosion, and two capsized during evacuation.

It was a Titanic-style tragedy: they believed the ship wouldn’t sink, so they skimped on safety. A terrible miscalculation.

The torpedo hit the starboard engine room. The engines stopped, power failed, lights went out, security doors jammed. Chaos followed.

But amid the chaos, there was a remarkable moment: a German naval commander (a prisoner), an English officer, and a Canadian officer worked together to manage the evacuation. They remained aboard, helping launch lifeboats in the dark, under fire, and all three died in the sinking.

It was a horrific tragedy. Over 700 people died, including more than 400 Italians, and at least one woman.

It was a tragedy that could have been mitigated—if not avoided—with better planning and less fear-driven urgency.

Now, we study these events with calm, pain, and respect for those who died, hoping such tragedies never happen again. Let this be a lesson to our politics to steer far from war—because war is not an exchange of chocolates, but of cruelty.

La Gran Bretagna era isolata e sola.

Gli Stati Uniti non erano ancora entrati in guerra. La Germania aveva già conquistato la Norvegia, la Polonia, la Danimarca, il Lussemburgo e la Francia. La Gran Bretagna era rimasta sola, un’isola, ed era il suo turno. L’Operazione Leone Marino, cioè il piano tedesco di invasione della Gran Bretagna, era in corso. I tedeschi erano pronti a invadere.

Il sostegno dell’Italia alla Germania fu un segnale inequivocabile.

E quindi, cosa fece la Gran Bretagna? Prese ancora più paura. Churchill, spinto anche da una campagna stampa che faceva riferimento all’invasione della Norvegia—dove un movimento interno aveva indebolito la resistenza facilitando l’invasione tedesca—diede un ordine. Si parlava di “quinta colonna”.

Anche gli inglesi credevano che una “quinta colonna” potesse esistere al loro interno. Non esisteva, non era reale, ma loro ci credevano. Così nacque l’idea che la quinta colonna fosse composta dagli italiani residenti in Gran Bretagna. Italiani residenti lì? Vennero considerati tutti fascisti. Quindi: arrestiamo i fascisti e portiamoli via.

Un’equazione semplice, nata dalla paura.

Era tutta paura—non che vada giustificata, ma bisogna capirla. La Gran Bretagna era sola e temeva di crollare. Churchill dichiarò: “Questo è il nostro momento più buio.” C’è perfino un bellissimo film che riprende esattamente quella frase. Gli Stati Uniti non erano ancora in guerra, quindi gli inglesi dovettero adottare misure straordinarie, diretta conseguenza della dichiarazione di guerra dell’Italia. Venne dato un ordine terribile: arrestateli tutti, prendeteli, mettetegli il collare, senza eccezioni.

Avevano già le liste pronte—prese da tutti i circoli italiani, molti dei quali legati alle Case del Fascio.

Ma facciamo chiarezza: le Case del Fascio a Liverpool, Manchester, Londra—perfino Glasgow—non erano come quelle in Italia. Erano semplici luoghi di ritrovo per italiani all’estero. Non si parlava nemmeno di politica. Per loro, la politica di Roma era lontana. Le chiamavano “Case del Fascio” perché quello era il governo italiano, ma in realtà erano ritrovi per famiglie italiane.

Gli inglesi avevano gli elenchi degli iscritti. E per loro l’equazione era: circolo italiano = fascista = simpatizzante = possibile spia. Quindi: arrestateli tutti.

Erano considerati potenziali sabotatori.

Questo tipo di azione non fu un caso isolato. La stessa cosa accadde negli Stati Uniti con i giapponesi: dopo l’attacco a Pearl Harbor, gli americani arrestarono i residenti giapponesi, anche nelle isole Hawaii, e li misero in campi di internamento.

Noi italiani facemmo lo stesso con gli inglesi in Italia, anche se erano pochi. Alcuni furono perfino portati a Villa Basilica—sei maltesi—perché considerati potenziali nemici o simpatizzanti.

Ma qui sta la tragedia: la comunità italiana in Gran Bretagna era perfettamente integrata. Vivevano lì, i figli andavano a scuola con i bambini inglesi. La mattina dell’11 giugno (dopo che Mussolini aveva dichiarato guerra la sera prima alle 18:30 da Piazza Venezia) iniziarono gli arresti. Tutto era già stato pianificato. Le operazioni furono immediate.

Anche i poliziotti inglesi si vergognavano: i loro figli giocavano a calcio con i figli degli italiani, vivevano nelle stesse case, lavoravano insieme. Non sapevano cosa dire.

Così, gli italiani furono portati in campi di internamento—ex caserme, aeroporti dismessi, spazi pubblici adattati alla meglio. Da lì, molti furono mandati all’estero: in Canada, in India, nelle colonie britanniche. Il Canada offrì inizialmente 4.000 posti.

La prima nave fu la Duchess of York, un po’ più piccola, che trasportò 2.000 persone e arrivò in sicurezza in Canada.

La seconda nave—ed è qui che inizia la tragedia—fu la Arandora Star, un’ex nave da crociera lussuosa, dotata persino di piscina. Fu requisita dalla marina militare, come molte altre navi civili durante l’evacuazione di Dunkerque. La marina inglese trasformò molte navi civili in militari.

Nella tradizione navale inglese, marina mercantile e militare condividono uniformi e gradi. La bandiera è la stessa, con l’unica differenza della corona.

Sulla Arandora Star vennero installati due cannoni: uno a prua e uno a poppa. La nave divenne così, ufficialmente, una nave militare.

Non era una nave da combattimento, non una fregata, non una corvetta. Non aveva corazze o armamenti pesanti. Ma con due cannoni a bordo, era una nave da guerra. A bordo c’erano circa 1.500 persone: 900 prigionieri, 200 militari di scorta, 180 membri dell’equipaggio. I numeri variano, anche per errori di trascrizione.

La nave partì per il Canada.

Ma va sfatato un mito: grazie ai documenti trovati da Balestracci e alle testimonianze, sappiamo che non è vero che i prigionieri furono trattati come bestie, rinchiusi tra filo spinato.

Il comandante della nave si oppose fin da subito al sovraccarico. Sapeva che la nave non poteva trasportare così tante persone. Ricevette l’ordine di imbarcarne 500 in più, ma riuscì a trattare con il comandante militare per ridurre il numero.

La nave seguì una rotta a zig-zag, per evitare i siluri. Era spenta, senza luci, come una nave da guerra. Non aveva segnali di riconoscimento. I pezzi d’artiglieria erano protetti da filo spinato per evitare che i prigionieri vi si avvicinassero.

Potevano dormire anche all’aperto. Ma la nave era sovraffollata—più del doppio della sua capacità.

Il 2 luglio all’alba, la nave fu intercettata da un sommergibile tedesco, un moderno U-47 tipo VIIB, comandato da Günther Prien, un eroe della marina tedesca.

Era già celebre per aver affondato una nave nella baia di Scapa Flow, in Scozia.

Prien aveva già affondato cinque o sei navi e stava rientrando. Gli restava un solo siluro, difettoso. Il meccanismo d’impatto era danneggiato. Eppure, dopo aver identificato la Arandora Star come nave militare—consultando insieme al secondo ufficiale i registri delle silhouette delle navi—decise di colpire.

Fece il suo dovere. Era un ufficiale. Colpì una nave militare, secondo la sua identificazione. Non gli si può attribuire colpa.

Il governo britannico, invece, fu chiaramente negligente. L’organizzazione del viaggio fu frettolosa. Troppa gente, troppe poche scialuppe—solo 14, di cui 2 distrutte dall’esplosione, 2 rovesciate durante l’evacuazione.

Fu un errore di calcolo, come nel Titanic: si pensava che le navi fossero inaffondabili, e si risparmiavano le scialuppe. Una follia.

Il siluro colpì la sala macchine di dritta. Le macchine si fermarono, l’elettricità venne meno, le porte di sicurezza non si aprivano. Fu il caos.

Ma in mezzo al disastro, avvenne un gesto straordinario: un comandante tedesco (prigioniero), un ufficiale inglese e uno canadese collaborarono per gestire l’evacuazione. Rimasero a bordo, aiutando a calare le scialuppe, e morirono insieme.

Fu una tragedia. Più di 700 morti, di cui oltre 400 italiani, e almeno una donna.

Una tragedia che si poteva evitare—con più prudenza, con più tempo, con meno paura.

Oggi la studiamo con calma, con dolore, con rispetto per i morti. Con la speranza che simili tragedie non accadano mai più.

E con un invito alla politica: tenere lontana la guerra. Perché la guerra non è uno scambio di cioccolatini, ma uno scambio di cattiverie.